As part of the Marine Science Field Course, you get to be a part of multiple of Cape RADD’s research projects. Despite not being able to scuba dive, I was able to contribute to most of these research projects. One in particular I grew quite fond of.

The project aims to add data to a previous study that was conducted by Craig Smith and Charles Griffiths (1997). This project looks into the predation of shark egg casings we find on the beach. Whilst we are focusing more specifically on four endemic South African Sharks (which includes the Puffadder shyshark, the Dark shyshark, the Leopard catshark and the Pyjama catshark), we do look for all egg casings. Sometimes even finding rare skate egg casings! With that said, in my experience, I have only ever found Puffadder Shyshark and Dark Shyshark eggs washed up on the beaches. This could be due to multiple reasons, but I think it could be due to the different structures the sharks are laying their eggs on.

Over the month of my field course, I got to explore multiple beautiful beaches around Cape Town (mostly in False Bay) to search for these shark eggs. In the end, I managed to master the technique of finding these small eggs, even at times spotting them from the corner of my eye. Although, all my tricks and skills I did learn from the shark master himself, Mark Fitzgibbon. The trick I discovered, is to first understand the structure behind the shark egg casings.

All of these shark egg casings have something called tendrils. Tendrils are these spiral attachments on the egg that the sharks use to attach the egg to different structures during their incubation period. However, these eggs can become dislodged due to age, weather or other disturbances. Usually, only empty shark eggs wash up on the beaches, so the tendrils seem to do their job for the entirety of the incubation period.

Now that we know about these tendrils and how they attach to different structures, you can usually find washed up eggs caught in different structures. This is usually around pieces of kelp that have been washed up or in the outskirts of the coastal vegetation. Don’t get me wrong, there is definitely the occasional egg stranded in the middle of the sand, but you just might have a better chance using the hack I mentioned before.

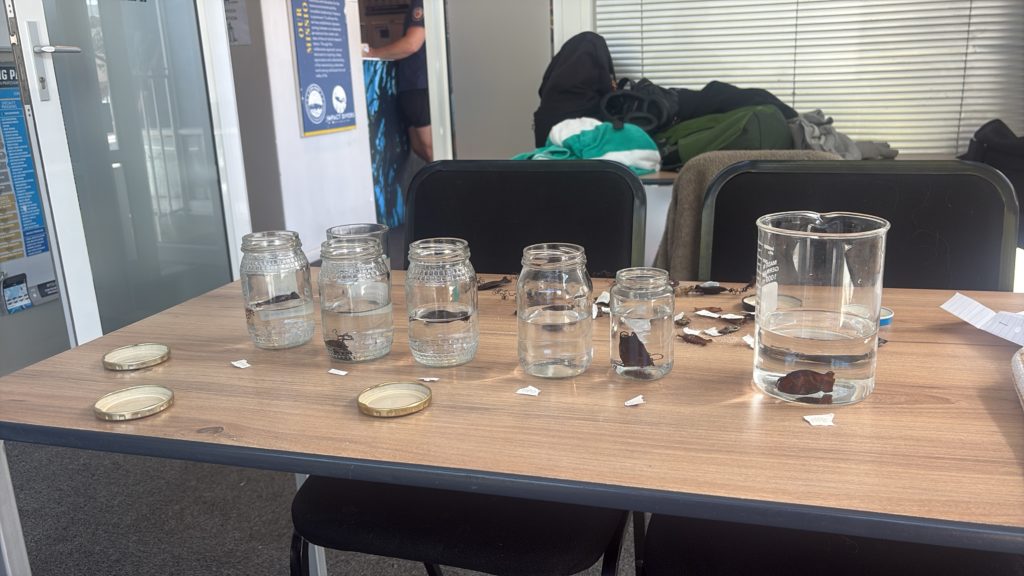

Once we have completed our collection (which can sometimes be zero eggs), we head back to the Ocean Hub (Cape RADD Headquarters) to analyse our eggs. Before measuring the eggs, we must rehydrate them in water so that then they are their full size as they shrink when dried. The eggs are ready when you are able to gently squeeze them a little bit. For each egg we measure the length, width, whether a predation hole is present and whether the shark has hatched or not. This is able to let us gain more understanding on whether predation has any correlation to egg casing size and if predation is increasing or not from when the original study was done. This information is vital to understand for the future of these shark populations. They can help provide insight into population numbers and may even help to guide future conservation efforts.

All in all, I will happily admit that I have found my new addiction. Finding shark eggs needs to be more talked about and how fun it is! I just can’t wait to get back out on the beach again.

References:

Smith, C. & Griffiths, C. (1997) ‘Shark and skate egg-cases cast up on two South African beaches and their rates of hatching success, or causes of death’, South African Journal of Zoology, 32(4), pp. 112–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/02541858.1997.11448441

0 Comments